It is with great sadness that I report the passing of Ian House, a long-time friend of Radio Dismuke and myself dating back to the very early days of the station.

Ian never appeared on any of our broadcasts, though listeners might recall either the late Eddie The Collector or myself giving a shoutout to Ian, who almost always tuned into our broadcasts.

Those who remember the old “Dismuke’s Message Board,” where anything related to vintage music and recordings of the early 1900s was discussed, might recall Ian, as he was a very active and prolific participant.

Others might recall or have heard of Ian through his work researching and bringing attention to the 1920s and 1930s female jazz and blues vocalist Lee Morse of whom Ian was a huge fan.

I got to know Ian a month or two after I started Radio Dismuke in early 2002 on a now-defunct platform known as Live365. Shortly after I started the station, I noticed another station had appeared in Live365’s directory that mentioned playing music from the 1920s and 1930s. I tuned in and noticed its playlist was similar in scope to mine. I reached out through the station’s contact info and extended my greetings and received a reply back from Ian House, who grew up in Canada and worked in Northern California for Electronic Arts developing video games. Thus began the first of many exchanges I had with Ian over the years through email, message boards, in person, and, eventually, Facebook.

I can’t recall how long Ian kept his station going, nor do I recall him ever mentioning that he had shut it down or why. I am quite sure that he spent far more time actively participating in my station’s message board than he did updating or promoting his own station. My guess is that Ian got enjoyment out of creating the station. But Ian had so many other talents and passions that, once he got it up and running, I suspect he had other things he preferred to spend his time on than expanding its playlist and audience and the various headaches involved in keeping a station going.

Dismuke’s Message Board was an online forum that was originally part of a vintage music website I operated before I started Radio Dismuke. For several years the board had a very active and growing membership of ’20s/’30s era music fans. Many of the posters were highly knowledgeable and sometimes would share information not available elsewhere. In a certain sense, however, it would have been accurate to have called it Ian’s Message Board, as much of the board’s success was due to Ian’s participation, though he was never an administrator nor had any role in operating it.

Ian was a natural when it came to online engagement. He would start new threads and respond to existing ones with postings that made people want to jump in and reply. His postings were informative, conversational, entertaining, and sometimes funny. I did not have the time to be as active on the message board as I would have liked. I mostly kept an eye on it in case there were any moderation concerns I needed to address – which, thankfully, were rare. Ian was the one who welcomed new members and would devise conversation-starting new threads when participation began to slow down.

One posting of his that I remember mentioned that he had just discovered a new website he found to be impressive and promising that allowed people to publish short videos, including those with music. The name of that website: YouTube. That was how I and probably a number of others on that message board first learned of YouTube’s existence!

Ian forged friendships with multiple members of the message board that endured well after I closed the message board. One of those friends was the late Edward Mitchell, a.k.a. “Eddie The Collector,” who participated in our broadcasts and, later on, became a board member of Early 1900s Music Preservation.

Sadly, I eventually had to close the message board after the constant need to contend with automated spam bots had become too time-consuming and burdensome. It got to the point the board was receiving hundreds of new user registrations daily, all from would-be spammers. By that time, Facebook was already starting to suck the oxygen out of a lot of independent message boards.

So I decided to lock the message board down but keep it online so that people could still discover and read its content. Unlike discussions of current events, discussions of vintage music rarely become outdated. The message board continued to enjoy traffic in view-only mode. There have even been a few instances when I was researching a topic only to find a posting from the message board in my search results.

Unfortunately, the message board suddenly stopped working a few weeks ago – I suspect because an update to the web server broke compatibility with the forum hosting software which, by now, is no longer supported. If it were still accessible, I would provide links to threads that would introduce Ian to those who have never encountered him.

Since I still have the database with all of the postings, I should, in theory, be able to find a way to get it up and running again. It is my intention to find a way to restore it. Not only does it contain a lot of information about vintage recordings, there was a lot of entertaining interaction between participants, several of whom, like Ian, are sadly no longer with us. I don’t know how long that will take, but once it is back up and running, I will put up an announcement on this blog.

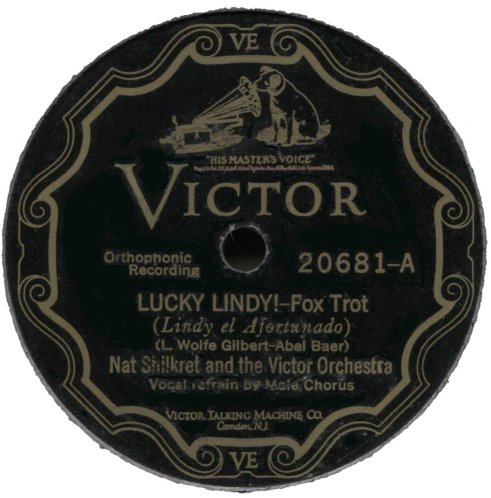

One of Ian’s contributions to the vintage music world was his work on researching and promoting awareness of the ’20s/’30s era female vocalist Lee Morse. Ian did not consider himself to be a big 78 rpm collector, but he spent several years seeking and buying Lee Morse’s records. This effort culminated in a 2005 two-volume CD set, Lee Morse: Echoes of a Songbird, issued by Jasmine Records, a jazz label based in London. That CD set remains in print and can be found on both Amazon.com and Jasmine Record’s websites.

The only aspect of the CD that was not Ian’s work was the audio restoration, which was done by professionals hired by Jasmine. But it was Ian who compiled the records and provided the raw transfers. He also wrote the liner notes and did all of the graphic design for the CD cover and booklet.

Ian also had a website devoted to Lee Morse where he documented much of his research into her life: http://www.leemorse.com/. As of this writing, the website is still active. However, since much of it was written to utilize Adobe Flash, which is no longer supported by modern browsers, most of the site’s content will be inaccessible without a Flash replacement. One such replacement is Ruffle, an open-source Flash emulator. If all one wishes to do is view old Flash websites, the easiest way to use it is to add the Chrome extension. Once I installed the Chrome extension, I was able to get the site to work.

Ian created another Lee Morse-related website as part of an effort to preserve the old Opera House in Kooskia, Idaho, where Morse had performed when she was a teenager. On that site, Ian shares details and photos about the period that Morse and her family spent in Idaho. He also shares videos he made while doing his reserch in the area. That site does not use Flash and remains fully functional: http://www.savetheoperahouse.com/index.htm

Ian also created a virtual museum he called The American Package Museum from his collection of vintage product packaging: http://www.packagemuseum.com/index.htm

I finally got to meet Ian in person during the summer of 2006, when he was in the process of moving from California to Noblesville, Indiana, where he intended to start his own business. He used the move as an opportunity to visit different parts of the US, including places relevant to his research on Lee Morse.

One of his stops was Fort Worth and North Texas, where Lee Morse had family ties and where she lived and performed between 1934 and 1939. I spent several days showing Ian various locations in and around Dallas/Fort Worth that had historical connections with Lee Morse. Ian and I also drove down to Waco, Texas, so that he could finally meet Eddie The Collector and Matt From College Station, who drove up from that city, both of whom he had interacted with on the message board and had listened to on our broadcasts. We spent an entire day with Eddie taking us to various historical sites in Waco, watching vintage musical short features, and listening to old records.

One of the highlights of Ian’s time in North Texas was getting to visit the old Baker Hotel in Mineral Wells. I gave Ian a tour of Mineral Wells on our way back from seeing an old wooden church building that once belonged to a congregation founded by Lee Morse’s grandfather, who was one of the early white settlers in what is now Palo Pinto County. Mineral Wells had been a nationally famous health resort in the late 19th and early 20th centuries but went into a steep decline after World War II. It is a small town dominated by the 14-story Baker Hotel, a once-luxurious resort hotel that opened in 1929 and had been abandoned and left to decay since 1972.

When I took Ian up the stairs to the hotel’s front porch so he could peer through the front door into its once-grand lobby, we discovered that one of the hotel’s local key holders was quitely offering anyone who passed by an informal, unofficial tour of the hotel’s lobby, mezzanine, and third-floor mineral baths for a few dollars per person.

Ian fell for the old hotel the moment he saw it. During our tour, Ian kept mentioning how much he would like to be able to see the rest of the hotel. The key holder said that it might be possible and provided me with his phone number so we could work out the details. When I called him back, we agreed to a price that would provide me and whoever else I wished to invite complete access to the entire hotel, with the keyholder accompanying us so he could point out interesting details and answer any questions.

Upon Ian’s return from his visit to other Texas cities, he, Eddie, and I met up in Mineral Wells. We were able to explore the entire building, from the decorative bell tower high above the 14th floor to the mechanical rooms in the hotel’s sub-basements.

Thirteen years later, in 2019, I shared a news story on my Facebook page about how a serious deal to restore the hotel had finally been put together. Ian was thrilled to hear the news and, in his reply to my posting, he mentioned getting to tour the hotel and described it as being among “the most exhilarating experience[es] of my life.”

The next and final time I met up with Ian was the following summer. He and Eddie had both heard me talk about the remarkable art-deco-era architecture in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that resulted from the enormous wealth in that city during its 1920s oil boom years. The three of us decided to meet there so I could show them the sights.

We spent an entire day visiting grand old skyscrapers and other buildings in Tulsa. The next day, we took to the road, and I showed them Pawhuska, an old oil boom town that is the capital of the Osage Nation and whose 1920s downtown remained remarkably intact, with its facades having mostly been spared the uglification of 1950s-1970s “modernization.” More recently, that town was where much of the movie Killers of The Flower Moon was filmed – a movie I recommend both for its story and its 1920s period setting.

We then visited Guthrie, Oklahoma’s old territorial capital and first state capital, which has one of the country’s largest intact Victorian-era downtowns. Then we visited Oklahoma City and dined in the 1911 Skirvin Hotel, which had just been restored and reopened after two decades of abandonment.

At the end of the trip, when we set off to return to our respective cities, it never occurred to me that it would be the last time I would ever see Ian. We talked about the three of us meeting up again sometime, but that never happened.

In the months since Eddie passed away last August, I have thought a lot about and shared a number of stories about the visits that Eddie, Ian, and I made to the Baker Hotel and to Oklahoma. It seems so odd to be revisiting those memories once again so very soon, this time because of Ian’s passing.

In many respects, Ian and I did not know each other all that well. I knew very little about his day-to-day life, and he knew little about mine. Our interactions were almost always limited to our shared passion for the music and aesthetics of the early decades of the 20th century.

But he was absolutely a great friend in terms of his encouragement and enthusiastic support of my efforts with Radio Dismuke. And I have no doubt that there are many people who consider themselves to be fans of Lee Morse who might not otherwise have heard of her had it not been for Ian’s efforts to bring attention to her music and career.

I do not know the circumstances surrounding Ian’s passing, but for the past couple of weeks, I had a feeling that something was amiss.

Earlier in the month, I learned at the very last moment that the great 1920s/1930s band based out of Germany, Max Raabe and Palast Orchester, was on tour in the United States and that one of the cities they would be stopping at was Indianapolis, close to where Ian lived. I sent him a quick message through Facebook about it in case he had not been aware of it.

A couple of days later, it occurred to me that Ian had not responded back, which struck me as odd as Ian was one of those people who tended to be quick to respond on Facebook. When I visited his profile and saw that his last posting had been in late February, I had a sad feeling that something was likely wrong. Some people, myself included at times, will go months without logging into social media. But such a lengthy absence in posting was not typical of Ian.

When I learned of Ian’s passing, I went back and looked at some of his old Facebook postings. One of them, which I vaguely remembered him putting up in May 2019, caught my eye and struck me as a bit haunting, given current circumstances. In it, he talks about the passing of the well-known musician Leon Redbone, who, it turned out, had been friends with Ian due to their mutual interest in Lee Morse.

Here is what Ian wrote in that posting:

RIP, Redbone :~(

I lost a close, personal friend today and the world has lost one of Lee Morse’s most devoted fans, … and one of her most dedicated researchers.

I first met Leon Redbone through my LeeMorse website. He reached out to me by email and eventually we began a series of long, marathon conversations by phone every month or so for a couple of years. He was an eccentric and intensely private night owl type. My phone would typically ring at about 11 pm, always with the same simple greeting: “Redbone!” … and then we’d chat about Lee until about 3 or 4 am. He was Lee obsessed. We listened to her recordings together, exchanged research stories and photographs … and many laughs as we speculated about our own theories in regard to Lee’s biography. She left us with a LOT of missing details that needed to be creatively filled in :~)

Lee was Redbone’s favorite female vocalist. On his website today, there is an announcement of his death in which he mentions wanting to share a couple of shots of whiskey with her now that they are in the same realm together. Don’t empty that bottle! Save some for me :~)

At the height of our time together, I was prodding Leon to host a tribute concert dedicated to Lee at the Kooskia Opera House in Kooskia, Idaho. Although I had his attention and his initial enthusiasm, unfortunately he was winding down his career. He had a fear of flying and always traveled around the country by car … and he was about a year away from the end of his travels.

The Kooskia concert would have been GRAND. I regret that we had not met just a few years earlier ::sigh::

Happy Trails, Redbone! Thank you for your warm friendship. Give Lee a kiss on the cheek for me ❤

And keep that whiskey bottle handy :~)”

Wouldn’t it be great if it were somehow possible for Ian to be with Lee and Redbone, enjoying some whiskey that they saved for him?