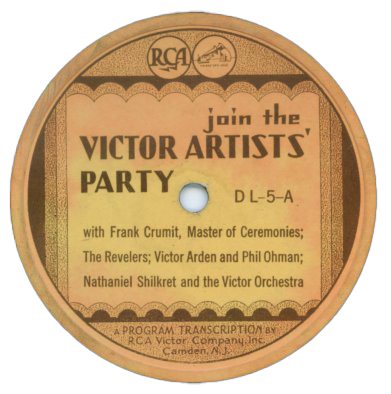

“Victor Artists Party”

Frank Crumit, announcer and vocal; Victor Arden & Phil Ohman; The Revelers; Nathaniel Shilkret & The Victor Symphony Orchestra

(Victor Program Transcription D L 5-A) July 30, 1931

“Dance Medley (You’ve Got Me Crying Again, Down A Carolina Lane, Honestly”)”

Isham Jones And His Orchestra; Joe Martin, vocal (“You’ve Got Me Crying Again” “Honestly”); Eddie Stone, vocal (Down A Carlona Lane)

(Victor Program Transcription L 16021) February 14, 1933

“Popular Selections (Home, Save The Last Dance For Me, A Faded Summer Love)”

Wayne King And His Orchestra; Tom, Dick & Harry, vocal

( Victor Program Transcription L 16000) November 23, 1931

Courtesy of Matt From College Station’s collection, here are recordings from three rare Victor Program Transcription discs, an early, commercially unsuccessful attempt at a 33 rpm long playing record a full 17 years before the advent of the modern LP record.

One of the big challenges since the dawn of the recording industry was the extreme time limitation of how much music could be made to fit on a record. The average 10-inch record during the 78 rpm era could hold approximately 3 minutes of audio on each side and 12-inch records could hold about 4 minutes worth.

There are only three ways to extend the playing time of a record: make the record larger, make the record’s grooves smaller, or slow down the speed. Victor’s Program Transcriptions were an attempt at the latter. The more commonly found 10-inch discs were able to contain up to about 10 minutes of audio and some were also issued in a 12-inch size.

The records differed from the later LPs in that they did not have microgrooves and they were either made out of shellac or, more commonly, a plastic material called “Vitrolac” which had a much noisier playing surface than the vinyl that modern LPs use.

Unfortunately, the new format was a commercial failure, largely because the records were introduced at the worst possible time when the Depression had still not reached its bottom. In 1932 Victor’s total record sales were only 10 percent of the label’s 1927 high point. All of Victor’s 1920s-era competitors had either folded or would be absorbed into the American Record Corporation. The only thing that kept Victor alive was the deep pockets of RCA which had purchased the label in 1929 and also owned the highly profitable NBC radio network.

Not only was it a bad time for selling records, because most record buyers were still using windup-style phonographs, they would have had to purchase a new record player to listen to them as they could only be played on a phonograph with an electrical pickup and capable of playing the slower speed.

Victor’s new machines for playing the records started at $274 (approximately $5,310 in 2024 dollars) and went up to $995 (approximately $22,343 in today’s dollars).

Needless to say, not many people bought the new records.

By 1934 Victor had stopped making new issues, though some of its existing ones continued to be listed in Victor’s catalog as late as 1939.

Oddly, Victor did not make a serious attempt to take full advantage of the new format’s benefits for the one market for which the records made the most sense: classical music, whose fans also tended to be more affluent. Unlike the issues featured here aimed at a popular audience which were specifically recorded for the format, most of the classical issues merely consisted of compilations of dubs from previously issued 78 rpm releases.

The 33 rpm speed did not die out completely before the 1948 introduction of the LP. 16-inch 33 rpm broadcast transcription discs that could hold 15 minutes per side were the standard format used by radio stations to capture and play pre-recorded programming into the 1960s when they were finally supplanted by tape recordings.

“Victor Artists Party” was the first Program Transcription to be issued and is a demonstration record introducing the new format. The record was also provided as a bonus for those who purchased Victor’s $350 (approximately $7,500 in 2024 dollars) RAE-59 model phonograph.

The announcer is Frank Crumit who was popular during the 1920s and early 1930s as a composer and singer of often folksy novelty songs. Also featured are the piano duo of Victor Aden and Phil Ohman, The Revelers, a vocal quintet whose records inspired the formation of the better-remembered German group, the Comedian Harmonists, and Nat Shilkret conducting Victor’s in-house orchestra playing Ferde Grofé’s “Mardi Gras.”

While all three of the songs featured in Isham Jones‘ “Dance Medley” disc were also issued on 78 rpm, the recording here was made separately during the same recording session. The band appeared on a few other Program Transcription discs as well. The selections on this are not at all jazzy but are a nice example of the more sedate “sweet” style of dance music that became popular during the early Depression years between the end of the Jazz Age and the dawn of the Swing Era. Matt played this disc on Radio Dismuke’s recent New Year’s broadcast.

The Wayne King Orchestra’s “Popular Selections” was the first record released in Victor’s L-16000 series of Program Transcriptions, which the Isham Jones disc was also from. These were lower-priced 10-inch Program Transcriptions that were single-sided and sold for 85 cents (about $18.25 in 2024 dollars). By contrast a double-sided popular series Victor 78 rpm cost 75 cents (about $16 in 2024 dollars).

Of the three Wayne King selections, the only one that was recorded separately for issue on 78 rpm was “Save The Last Dance For Me.”

The Wayne King disc was recorded in the ballroom of the old Webster Hotel in Chicago, a venue that Victor utilized for many of its recording sessions in that city. Happily, the hotel’s building still stands and now houses apartments. You can see photos of its spectacular still-intact 1920s lobby at this link.

I was not able to learn if the hotel’s ballroom survives but, as this recording demonstrates, its acoustics were amazing. For whatever reason, during the early years of electrical recording, American record labels tended to heavily dampen their recording studios compared with their European counterparts. But, on this recording, particularly towards the beginning, the room provides just enough echo effect to make it come to life.

Imagine what such a band must have sounded like in the 1920s and 1930s live in such a ballroom without the limitations of the era’s recording technology (and the fidelity of these Program Transcription discs was even less than that of Victor’s 78 rpms of the period).

– Dismuke