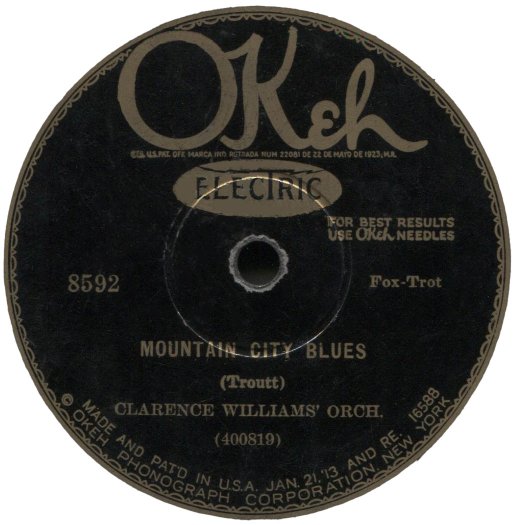

“You Told Me To Go”

The Knickerbockers

(Columbia 482-D mx 141140) October 16, 1925

“Don’t Wait Too Long”

Eddie Elkings And His Orchestra

(Columbia 482-D mx 14114) October 7, 1925

From the Edward Mitchell collection, here is what I think is a fun record – particularly the “You Told Me To Go” side, which is reflective of the mid-1920s Charleston craze that was at its height when this record was made.

For anyone needing recordings that exemplify the 1920s decade’s “Roaring ’20s” spirit, this version of “You Told Me To Go” is definitely one to add to the list.

“The Knickerbockers” was one of many recording pseudonyms for Columbia’s in-house band led by Ben Selvin.

Interestingly enough, the Knickerbocker name had previously been used on Columbia records in 1921 and 1922 for certain recordings by Eddie Elkin’s Orchestra, who perform on the flip side of this record. Those recordings were issued as “The Knickerbocker Orchestra (under the direction of Eddie Elkins). ”

When those 1920 – 1921 recordings were made, Elkins’s band regularly appeared at the Knickerbocker Grill at Times Square, located in the basement of the former Knickerbocker Hotel. The 1906 Beaux-Arts-style hotel closed in 1920 and was converted into an office building. But the hotel’s basement grill, a popular night spot, remained open despite a few attempts to close it for alleged violation of Prohibition laws. (The building was converted back into a luxury hotel in 2015.)

Elkins was a classically trained violinist, and most of his band members during the period it performed at the Knickerbocker Grill had previously worked as musicians for the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra. Some of his Columbia recordings while his band was at the Knickerbocker were issued as The Knickerbocker Orchestra and others as Eddie Elkin’s Orchestra.

“Don’t Wait Too Long” comes from Elkin’s second-to-last recording session with Columbia. His final recording session was held later that same month.

Elkins and his band appeared in several musical short feature films, one in 1929 for Paramount, which starred Eddie Cantor, and four more for Pathe in 1930, one of which starred a not-yet-famous Ginger Rogers.

Elkins’ only other recording session after leaving Columbia in 1925 occurred in 1934, and produced four sides, all of which were issued on the Perfect label.

I do not know what, if any, connection to Elkins or the Knickerbocker Grill Columbia personnel had in mind when they came up with The Knickerbockers as one of the pseudonyms for its in-house band. It was used on many issues into the early 1930s. The term Knickerbocker had long been associated with New York City, so its use might have been entirely coincidental.