“Love Bird”

“Selvin’s Dance Orchestra”

(Aeolian-Vocalion-B 14155) Circa January-February 1921

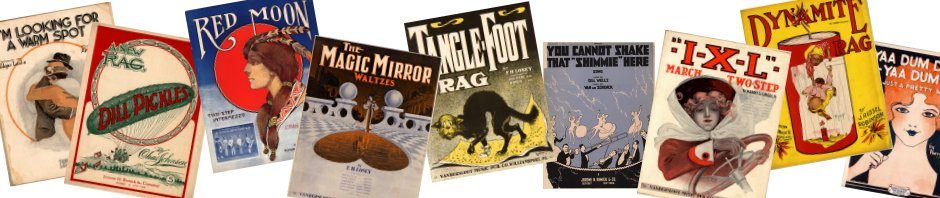

Popular music styles and trends evolved at an amazingly rapid pace during the early decades of the 20th century. The late 1910s and early 1920s were a transition period between the ragtime era and the Jazz Age.

When the ballroom dance craze that would endure and dominate popular music in the West into the early 1940s burst upon the scene in the early 1910s, ragtime was the dominant inspiration behind the new dance music, which was then primarily performed by large military-style bands.

By 1917, the first jazz recordings were issued, and very early dance bands were starting to emerge. They were smaller than the old military bands and used a different range of instruments to provide a lighter, less formal sound.

Increasingly, the arrangements used by these dance bands drew their inspiration from the new jazz music – so much so that, in the 1920s, it became common for people to refer to all dance bands as “jazz bands.” While not accurate, there was an element of truth in that almost all jazz musicians and even the jazziest bands of the period earned their living primarily by performing before live audiences who expected to be able to get up and dance to the music.

Here’s an early 1921 dance band recording from the Edward Mitchell collection that I think is rather charming.

Compared to other dance band recordings of the period, its arrangement is conservative and there is a particularly noticeable holdover from the ragtime era. Observe that the recording essentially consists of the same musical passages being repeated until it is time for the record to end. Unlike many ragtime-era dance recordings by groups such as the Victor Military Band and Prince’s Orchestra, it does provide a different orchestration each time the music repeats – but it never strays very far.

By this time, dance band arrangements were already evolving to become more varied, creative, and willing to stray from the standard stock rendition issued by the music publishing houses. Arrangements would also begin to feature more solo passages, and bandleaders would allow their top musicians the freedom to improvise on such solo passages.

By the time the microphones started being used on the first electric recordings four and a half years later, the Charleston craze was underway, and arrangements like the one heard on this recording were already considered out-of-date. By the start of the 1930s decade, they were considered to be hopelessly old-fashioned.

Though these early dance band recordings quickly fell out of favor and are often overlooked even by many 78 rpm collectors, a lot of really nice records were made during this period, especially if one is willing to listen to the recordings on their own terms and not through the lens of where recording technology and music eventually evolved by the end of the decade.

What I like about the dance bands of the early 1920s is that many of their recordings – including this one to a degree – had a certain unique sound that lasted only for a brief period and that I can only describe as charming and/or haunting.

“Love Bird” was composed by bandleader Ted Fio Rito and Mary Earl, a pen name for male composer Robert A. King. The song was successful, and almost every record label at the time issued at least one version.

Ben Selvin holds the world’s record as the most prolific recording artist, having recorded over 9,000 sides between 1919 and 1934 (some estimate the number is closer to 20,000), both under his own name and under a staggering array of pseudonyms.

One cannot tell by looking at the label image, but the playing surface on Vocalion records during this period was reddish-brown due to dyes mixed into the shellac. The Aeolian Company, which manufactured Vocalion phonographs and records, billed them as “Vocalion Red Records.” The company’s promotions from that period often featured the slogan “Red Records Are Best.”